Why You Should Care About Elixir

Mar 29 2018

This is a collection of notes from when I presented a short introduction to Elixir in a programming languages course. These notes provide a drive-by view of Elixir and don’t touch on the interesting parts like the Actor Model and other patterns. For a more in-depth introduction, see the main Elixir documentation.

Introducing Elixir.

Elixir is one of the most well thought-out languages around. It’s young (from 2011), but it’s already a huge game-changer, especially in the world of functional web development.

Install Elixir, and lets get started.

First thing’s first about Elixir: pattern matching.

Pattern Matching

As a functional language, assignment doesn’t exist. Instead, everything in

Elixir is done by matching left and right hand sides of equations, like math.

Crack open iex on the command line.

iex> a = 1

1Nothing looks odd here at all. What about this?

iex> 1 = a

1Did you just assign a to the value of 1? No! With Elixir, the left

and right sides just have to match. Now that we know that a is 1,

what if we do this?

iex> 2 = a

** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: 1This seems really odd. Why on Earth would you use this?

Destructuring

We’ve all been in this place before. You have a big map in your hands and you need to get an element waaaayyyyy inside it. You can do this:

variable.request.body.header[0]["foreign-address"]But this is slightly ugly. With Elixir, you can break down complicated data structures into their components with pattern matching.

iex> list = [1, 2, 3]

[1, 2, 3]

iex> [a, b, c] = list

[1, 2, 3]Woah. That’s a lot of variables all at once. Check them out.

iex> a

1

iex> b

2

iex> c

3You can take apart a list by matching it to variables.

But what if we don’t know exactly how long the list is?

iex> list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

iex> [a, b | tail] = list

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

iex> a

1

iex> b

2

iex> tail

[3, 4, 5, 6]The | operator allows us to split a list. With it, we can

perform tons of cool recursive functions on lists.

iex> defmodule Sandbox do

...> def list_length([]), do: 0

...> def list_length([_head | tail]), do: 1 + list_length(tail)

...> end

iex> Sandbox.list_length [1, 4, 5, 8, 11, 674]

6Try this in iex:

iex> defmodule Factorial do

...> def of(0), do: 1

...> def of(n), do: n * of(n - 1)

...> end

{:module, Factorial, <<70, 79, 82, ...>, {:of, 1}}

iex> Factorial.of 0

1

iex> Factorial.of 6

720

iex> Factorial.of 100

3628800Cool! What exactly happend there?

Modules

Modules are the namespaces of Elixir. You can define modules inside of modules, extend them in different files, and pretty much anything you want. They combine the organization of C++ namespaces with the extensibility of JavaScript prototypes.

In an Elixir program, you’d make one with:

defmodule ModuleParent.ModuleName do

defmodule SubModule do

end

endEvery module has a capitalized name. You can nest them inside eachother or

use the . notation. The full name of the innermost module here is

ModuleParent.ModuleName.SubModule.

A few other standardized stylistic choices of Elixir modules:

- Singular

- Start with a capital letter

- Are CamelCase

def

def is the most magical keyword of Elixir. It allows you to define

functions.

Everything in a module is a function; there are no internal members. If you

want to store a big set of data (for testing purposes, e.g.), you could

do this:

defmodule Factorial do

def test_data do

[0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 122, 8675]

end

endSo is test_data a variable? No! It’s a function. More properly, it shoud

be like this:

...

def test_data() do

...

...test_data is really just a function that returns the list.

The more common use of def, though, is for functions.

defmodule Factorial do

def of(0), do: 1

def of(n), do: n * of(n - 1)

endHere, of is the function and it takes a single argument. It’s overloaded

here, though, because of pattern matching. Elixir will first check if

you’re calling it with a 0. If it’s a zero, it’ll give you that clause. If

there’s no match, it’ll continue on to try the other functions of the same

name. What if you defined the module like this?

defmodule Factorial do

def of(n), do: n * of(n - 1)

def of(0), do: 1

endTry it out! Write that to a file and use c "filename.exs" in iex.

iex> Factorial.of 5Your computer might chomp on this for a while. In fact, it’ll just go

infinitely or until you get a Stack Overflow. The first case of the function

always matches, so it’ll just recursively call the next smallest number

forever. That means the order of def clauses matters.

Don’t worry, though. It’s pretty easy to tell if you’re about to do this. Elixir gives you the warning:

warning: this clause cannot match because a previous clause at line 2 always matchesPiping and Functions

The most magical character in all of Elixir, nay, in all of programming is

the pipe |>. Piping allows you to make your code exceptionally readable

and extendable. Let’s try it out.

iex> times10 = fn n -> n * 10 end

#Function<6.99386804/1 in :erl_eval.expr/5>

iex> times10.(5)

50

iex> 5 |> times10.()

50The first thing to notice is the anonymous function fn. We can construct

any sort of function with fn.

iex> less_than_5 = fn n -> n < 5 end

#Function<...

iex> less_than_5.(6)

false

iex> less_than_5.(4)

trueAnd call the function with the preceeding dot and parentheses. Also notice that previously we haven’t used the parentheses around the arguments. With anonymous functions, though, you need to.

Now the pipe operator. The difference between times10.(5) and

5 |> times10.() is pretty straightforward. The five is just now

outside the function’s parentheses. Things get more interesting when

you have multiple functions.

iex> times10 = fn n -> n * 10 end

iex> add3 = fn n -> n + 3 end

iex> 5 |> times10.() |> add3.()

53The |> operator is actually a macro. Macros are functions that produce

and alter code. |> here takes this:

5 |> times10.() |> add3.()and converts it to this:

add3.(times10.(5))In the end, the former is exactly as performant as the latter because when they’re executed, they’re the same.

Tooling

Elixir has amazing toolset. It’s one of the reasons Elixir has grown in popularity so rapidly. Specifically, Elixir has great documentation, build tools, and package management.

Lets start with the build tool: mix.

Mix can create, compile, and test your project.

$ cd

$ mix new elixir_noob

$ cd elixir_noob

$ mix deps.get

$ mix test

$ mix compileYou can also use mix to compile your elixir scripts into command line executables using Erlang e-script. It requires a little configuration of the project, but eventually, you can do this:

$ mix escript.build

$ ./elixir_noob arg1 arg2 arg3 ...Mix doubles as the package manager, for the client side. The main repository of Elixir packages is Hex, which also can serve out Erlang projects. Here’s a project I created to test out Elixir’s tooling.

# xenium.ex

defmodule Xenium do

@moduledoc """

An XML-RPC client for Elixir.

Xenium simply combines the functionality of the HTTPoison and XML-RPC

libraries so you can get stuff done.

"""

@doc """

Post the XML-RPC server URL with a method name and optional parameters.

Returns a tuple of `{ :ok, response }` or `{ :error, message }`, where the

error tuple contains either the error response from HTTPoison or the

XML-RPC library.

"""

@spec call(binary, binary, list) :: { :ok, any } | { :error, any }

def call(url, method_name, params \\ []) do

# safely pipe the results of each

encode(method_name, params)

|> post(url)

|> decode

|> get_resp

end

defp encode(method_name, params) do

%XMLRPC.MethodCall{method_name: method_name, params: params}

|> XMLRPC.encode

end

defp post({ :ok, body }, url) do

try do

HTTPoison.post(url, body)

rescue

CaseClauseError -> {:error, "HTTPoison error. Probably a nil URL."}

end

end

defp post(_url, error), do: error

defp decode({ :ok, %{ body: body } }), do: XMLRPC.decode(body)

defp decode(error), do: error

defp get_resp({ :ok, error = %XMLRPC.Fault{} }), do: { :error, error }

defp get_resp({ :ok, %{ param: resp } }), do: resp

defp get_resp(error), do: error

@doc """

Post the XML-RPC server URL with a method name and optional parameters,

raising an exception on failure.

The functions used in the pipeline are `encode!` `post!` and `decode!`,

which all raise exceptions on failure.

"""

@spec call!(binary, binary, list) :: any

def call!(url, method_name, params \\ []) do

%XMLRPC.MethodCall{method_name: method_name, params: params}

|> XMLRPC.encode!

|> (&HTTPoison.post!(url, &1)).()

|> Map.get(:body)

|> XMLRPC.decode!

|> Map.get(:param)

end

endAnd the command line interface:

# /xenium/cli.ex

defmodule Xenium.CLI do

@moduledoc """

Handle command line operations for use as a local executable.

"""

@doc """

Entrypoint for the app if compiled into an executable.

Pipe the argument vector through `parse_args/1` and `process/1`

"""

def main(argv) do

argv |> parse_args |> process

end

@doc """

Parse command line arguments.

`argv` can be `-h` or `--help`, which returns `:help`.

Otherwise, it tries to parse out the URL, method name, and parameters.

Returns a tuple of `{ url, method, params }`, or `:help`.

"""

def parse_args(argv) do

parse = OptionParser.parse(argv, switches: [ help: :boolean ],

aliases: [ h: :help ])

case parse do

{ [ help: true ], _, _ } -> :help

# params will always be a list, [] default

{ _, [ url, method | params ], _ } -> { url, method, params }

_ -> :help

end

end

@doc """

React to the command line arguments.

Print the help dialog if help is needed. Call the client function otherwise.

Accepts either the `:help` atom or a tuple of `{ url, method, params}` where

params is a list.

"""

def process(:help) do

IO.puts """

usage: xenium <URL> <method-name> [ <param1> <param2> <param3> ]

"""

System.halt(0)

end

def process({ url, method, params }) do

Xenium.call!(url, method, params) |> IO.inspect

end

endIt’s a really simple program that allows you to call XML-RPC, a protocol for calling functions on other machines with other code bases. This library combines two other libraries: an HTTP client library and an XML-RPC decoder/encoder.

Notice all the areas of @doc and @moduledoc. These allow you to write

your documentation, like Doxygen for C++ and Javadoc for Java. The format

is standardized: it’s Markdown, like in GitHub README’s.

To produce documentation, just use mix docs, and open up docs/index.html.

Also notice how easily each program breaks down. Both files have main

functions like main in the CLI and call and call! in the other

file. These main functions use a pipeline to take input in and transform

it out. The the most important functions in the program are small and

readable. You’re taking the argument vector, parsing it, and processing

what you saw. The functions are split up for functionality too. process

has a body for when you’ve asked for help and another body for taking the

proper arguments. Divide and conquer.

Now check out this. That’s this library uploaded to Hex. You can check out the documentation, download it, and see the source in GitHub.

Phoenix

Phoenix is (arguably) the reason that Elixir is so popular. Phoenix is a backend. It serves webpages and API’s. The head turning part about it is the speed.

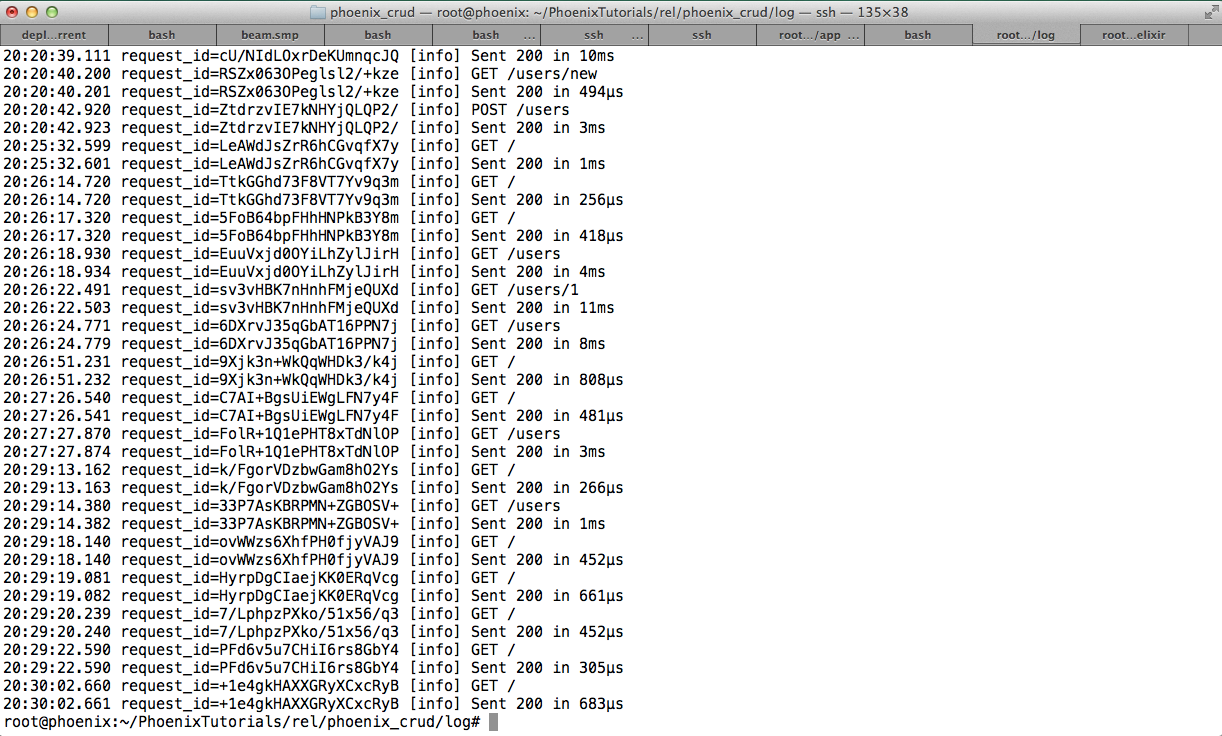

On average, an Apache backend might serve a static site with a response time of 900 microseconds. That’s really fast. That’s so fast that it’s pretty much instantaneous.

Phoenix, on the other hand, takes about 300 microseconds for the same content.

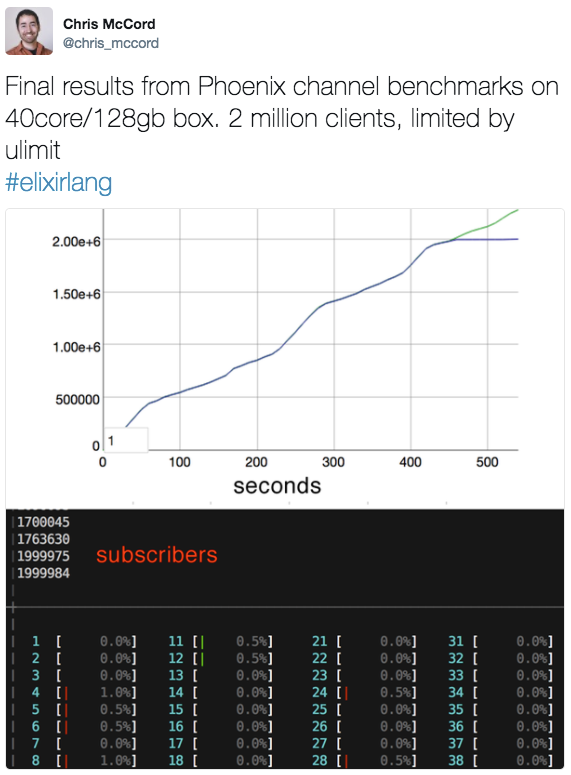

Even better, it can serve over 2 million clients with almost no impact on the CPU. Whatsapp even runs on the same VM.

It’s fault tolerant, too. Crashing one webpage (a 500 level HTTP response) leaves the rest intact. Why?

Erlang’s BEAM VM spawns off processes to do jobs asynchronously, like to serve a webpage. With languages like JavaScript, Go, Java, PHP, C++, and more, threads and new processes are pretty expensive. They cost a huge time overhead, which usually makes them inefficient for quick serving. The BEAM VM is built on spawning process. There’s virtually no overhead, so there’s really no reason not to spawn off new processes for everything. You can have multiple millions of processes without taxing the physical system.

But what exactly does a Phoenix app look like? Exactly what an Elixir app looks like! After installing, try this out:

$ mix phx.new

$ mix deps.get && mix compile

$ mix phx.serverYou’ll start serving a page immediately! Here’s the router for my website:

defmodule McdWeb.Router do

use McdWeb, :router

pipeline :browser do

plug :accepts, ["html"]

plug :fetch_session

plug :fetch_flash

plug :protect_from_forgery

plug :put_secure_browser_headers

end

pipeline :api do

plug :accepts, ["json"]

end

scope "/", McdWeb do

pipe_through :browser # Use the default browser stack

get "/", PageController, :index

resources "/projects", PostController, only: [:index, :show]

get "/topics", TopicController, :index

get "/vigilo", VigiloController, :index

end

scope "/api", McdWeb do

pipe_through :api

post "/vigilo", VigiloController, :update

end

endI wrote exactly 4 lines of that. Phoenix is a framework, meaning that most of the code is written for you. All you need to do is create content and add design and your site is good to go.

Adding new pages is quick and easy. Database management is built in and in “dev” mode, any changes to the code are hot-swapped into the server. With a framework like this, you can create strong fault tolerant servers with database operations, authentication, and clean asset management in under 20 minutes.

Conclusion

With most languages, writing good code is like this:

The first 90 percent of the code accounts for the first 90 percent of the development time. The remaining 10 percent of the code accounts for the other 90 percent of the development time.

Tom Cargill, Bell Labs

With Elixir, it’s a consistent and fast process. There’s virtually no

boilerplate code, and any boilerplate there that remains is generated

for you by mix.

Elixir is fast, easy to learn, and fun to use. If you’re interested, check

out the book.

I didn’t touch on some of the most interesting topics like GenServers and

OTP applications, macros, or systems tools, but they’re in there.

Disclaimer: Elixir may make you hate other langauges.